Following the 9/11 attacks and the launch of the Global War on Terror, many humanitarian policy wonks spoke of a new era of heightened aid instrumentalization – that is the use of humanitarian action or rhetoric as a tool to pursue political, security, development, economic, or other non-humanitarian goals, which would muddy humanitarian principles and constrain access to those in need.

But a new book, The Golden Fleece, argues that instrumentalization goes back centuries. The only thing that has changed is the “centrality and sheer size” of the humanitarian enterprise, says its editor Antonio Donini, senior researcher at Tufts University’s Feinstein International Center. “There never was a golden age of humanitarianism,” he says.

While aid agencies balked at Colin Powell’s description of them as “force multipliers” in the US “war on terror”, he was not far from wrong, says Lt-Gen (rtd) the Honorable Roméo Dallaire, head of the UN assistance mission in Rwanda during the genocide and author of Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda.

US aid agencies, for instance, were used as “force multipliers” in the Vietnam war and in the Central American civil wars of the 1970s and 1980s, to give but two examples.

“Humanitarians have been used… as fig leaves to veil government action and inaction in the face of war crimes and genocide. Humanitarians have been paid, manipulated, and `embedded’ with singular disregard for humanitarian principles. They have been routinely ignored, even in cases of obvious humanitarian need and enormous public outcry. They have been silent when they should have spoken out, and they have spoken out when they should have remained silent. They have called for military intervention… and on the few occasions when they got their wish, they mostly lived to regret it,” says co-author Ian Smillie, a long-time aid critic and founder of Canadian NGO Inter Pares.

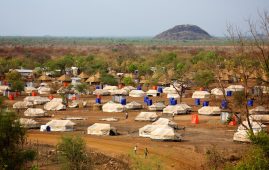

The Golden Fleece explores different forms of aid manipulation starting in the 19th century, and progressing to the 20th and 21st centuries, presenting a series of case studies in Sudan, the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Somalia and Haiti, among others.

Instrumentalization can also be more subtle – for instance when humanitarian emergencies are largely ignored by aid agencies and governments alike – or, in the case of food aid, when it is used to dispose of surplus stocks, to create new markets and to win over governments, as opposed to more blatant manipulation involving say, the diversion of stocks by warring parties.

“Dunanist” versus not

An increase in the number and severity of crises, the vast growth of the humanitarian sector, the increased ability of governments to dictate the shape of agency programming, the more intense real-time scrutiny, and the impact this has had on funding, have made agencies more aware of aid instrumentalization.

Some agencies stick to the humanitarian principles of independence, impartiality and neutrality more strictly – notably the “Dunanist” agencies International Committee of the Red Cross and NGOs such as Médecins sans Frontières (Henri Dunant inspired the creation of the Red Cross movement at the battle of Solferino).

However, even the ICRC has struggled to uphold its principles at times: for instance, by failing to step up its protection response to victims of concentration camps in 1930s Germany; or in keeping silent about British-run concentration camps during the 1890s Boer war.

For multi-mandate agencies – both NGOs and UN – neutrality, independence and impartiality “are more guidelines than principles. For them, manipulation… has been the default position, some using and some eager to be used,” says the book.

The danger for them is that in a place like Afghanistan, “some multi-mandate agencies may find themselves in a bind,” says Donini. “They want to do humanitarian aid at one point, but having been implementing partners for the government, for military-political provincial reconstruction teams, they are realizing these chickens will come home to roost.”

Instrumenalization of aid is more obvious in some crises than others. In Somalia all local groups – from local NGOs to businessmen to warlords – have sought to manipulate assistance to project their authority or enrich themselves, say the authors.

Lessons for aid agencies

The authors refrain from being prescriptive, but some lessons do emerge. A clear one is that calling for military intervention is almost always regretted later on. “Agencies call for the cavalry at their peril,” says Smillie, “This is a cautionary tale.”

Another is that aid agencies too often compartmentalize or simplify their view of a complex emergency, perpetuating a self-referential reality in which their solutions (food, tents), define the problem. This can often lead them to ignore the real problems at hand (human rights abuses, say, in Sri Lanka, or feeding genocidal killers, say, in Rwanda).

Such a vision leads Darfur to be depicted as a relatively straightforward tale of “bad” Arabs and “good” Africans rather than a more complex power struggle over land and water.

It also blinds them to their own impact: several researchers have asserted that humanitarian aid prolonged the war in Nigeria’s Biafra in the 1960s – a conflict in which an estimated one million people died, the majority as a result of malnutrition. Of course hindsight is a wonderful thing, but Smillie, who was there at the time, says several NGOs were aware of this dynamic at the time.

Perhaps one of the most useful lessons is that, in the authors’ analysis, manipulation of assistance generally does not get the manipulators what they want. “The fact that aid can be a force multiplier may be wrong,” said Smillie. Studies have shown for instance, that humanitarian aid in Iraq and Afghanistan did little to win over hearts and minds. Perhaps its very ineffectiveness should be an incentive to loosen the hold.

As Western power wanes and crisis-affected countries begin to assert their right to control crisis response, new dynamics will arise. Donini gave Sri Lanka as an example of where its leader Mahinda Rajapakse used the Global War on Terror and respect for sovereignty rhetoric to justify overwhelming force against the Tamil uprising when he came to power in 2005, out-manoeuvering and repressing humanitarians.

Long on problems and short on solutions, the book can make for depressing reading. But Donini stressed a final point: “This book focuses on the negative – we wanted to unscramble instrumentalization. But we shouldn’t deny all the positive…. there is much about the humanitarian enterprise that is really quite good.”

Q&A with authors of The Golden Fleece

IRIN discussed some of the book’s themes with its authors Donini (AD) and Smillie (IS).

You say aid instrumentalization is nothing new, but has it become more pronounced?

AD: There was never a golden age and there always has been instrumentalization of one kind or another. It is part of human nature to try to take advantage of assistance – be it by aid agencies, donors, warring parties or affected communities.”

IS: We [the authors] had been talking off and on over 10 years about how there was more and more instrumentalization – the sky was falling – and I wondered if it was cyclical. I thought there might have been a surge at the end of the Cold War, when there were more Western boots on the ground. But when I started to look at it I realized that was not the case – I was surprised by how similar many situations were. Instrumentalization was blatant among American NGOs in Vietnam in the 1960s and among the Atrocitarians in Bulgaria in the 1860s. The same could be said of Afghanistan and Iraq. The day before 9/11 there were hardly any Western NGOs in Afghanistan, despite great needs. The sudden outpouring of aid clearly had a lot to do with Western political and security interests. The point to show was that it was just part of an ongoing struggle between principles and the exigencies of politics and war.

Is a clearer separation needed between Dunanist and multi-mandate agencies?

AD: For me it makes sense to have a clearer separation between agencies that maintain a narrow humanitarian profile and are the only agencies that can cross lines and access fraught environments, and the rest of the aid community, which do important things but also take on human rights, peace building, state-support etc… We need a clearer definition of who is working according to these recognized principles and who is not.

IS: Should you take military protection to get a food convoy through? Some would say no. Others would say: people are hungry and if we don’t, they’ll die. There is a place for both [approaches].

How is the push for better accountability shifting the game?

AD: We are clearly improving accountability in how aid is provided, with standards (Sphere, People in Aid); access through proxies; real-time feedback; using mobile phones and video conferencing which allow agencies to check on stocks and verify if a sample of the population are receiving assistance. We have access to the Internet, to budgets, to standards, and can compare responses between different crises. When I was in Helmand Province in Afghanistan in June last year, I talked to the Afghan director of an NGO – he knows everyone there. A Taliban member summoned him to his house to discuss a water project that he had a problem with. When asked how he knew about the project, he said they were checking different NGO budgets to see where the money was coming from – whether from belligerents or independent forces…. It will become more difficult for agencies to pretend they are humanitarian when they are not. The days of arrogance characterizing the aid community – when you could fudge these issues – are gone, and that is a positive thing.

Where a lot of work is still required is working on the basis of evidence rather than hunches. Very often we come in and dump assistance without doing the proper assessments. Sometimes less is more.

Why are humanitarians not more aware of being used/using others?

AD: We’re very good at using the tools of the last crisis for the new one but are not good at adapting to new situations. That is why in places like Syria we are stuck. Should humanitarians be playing a more important role or are they just carrying the can for the failure of UN member states to find a solution?

IS: The problem among humanitarians is that they think the world began the day they arrived. They don’t know enough about the history and culture of the place, or of their business. We need to think about how lessons from the past apply in the current situation. I don’t know if there is a Biafra lesson that could be applied to Mali right now. There may be none, but it doesn’t hurt to be more literate in history of humanitarian action. Basically, this is just a lot of common sense, which is usually sorely lacking in an emergency setting.

How will dynamics shift in the future?

AD: Humanitarianism is in some ways a victim of its own success… Humanitarianism has grown in parallel with Western dominance… Now the West is in retreat, then maybe we are reaching the limits of Western modern humanitarianism?

What is emerging in parts of the world – Sri Lanka or Darfur for instance – is a more robust manifestation of sovereign nationalism… It is good that middle-income countries are more involved in defining how they will address humanitarian needs, but it is less positive that we risk a dilution or a manipulation of humanitarian agencies as a result.

India, China and other middle-income countries will start using their own soft power to advance humanitarian activities. Future crises – taking place in mega-cities, dealing with the impact of climate change – are those where the state is likely to be at the centre of the response, for better or worse. Aid agencies have traditionally been state-avoidant – this will have to change.

***********

* Originally published on IRIN (the humanitarian news and analysis service of the UN-OCHA), on Feb. 19, 2013, titled ‘The use and abuse of humanitarian principle’. Items from IRIN are published in this blog with a written permission to do so. Yet, this doesn’t necessarily indicate an endorsement of the claims therein.

Check the archive for related posts.

iphone メール フォルダ