Mehari Taddele Maru[1]

(Originally published in January 2010)

1. Introduction

Current discussions on Africa–China relations unsatisfactorily focus mainly on China’s interests in Africa and its unconditional assistance extended to undemocratic governments in Africa. Therefore, it is important to discuss bilateral trade and China’s interests in Africa particularly in terms of the former’s energy insecurity and its role as the spoiler in African conflicts. It is also important to criticise the relatively poor quality of Chinese manufactured products and work on infrastructure in Africa. The issue of Chinese migrants to Africa and their impact on local labour markets is also useful. Furthermore, there is a need to study how to improve the transfer of technology and skills from China to Africa. Also, many Africans are interested in the lessons Africa can take from the unconventional development growth that China has registered in the last three decades.

In 1978, China initiated a political strategy to build a dynamic economy. There were three stages to this strategy: doubling gross domestic product (GDP) in ten years to feed and clothe the population; redoubling GDP in 20 years to achieve prosperity; and in 70 years making the Chinese economy a global modern economy.[2] Currently, per capita income has increased five-fold.

There are two factors behind this near-miraculous growth: (1) capital asset accumulation through high domestic saving, and (2) the high productivity of China’s workforce through training.[3] Traditionally, the main driving element for economic growth was considered to be capital and free competition among market forces. According to conventional economic thinking, productivity was never seen as the prime force for economic growth. This increase in productivity is a distinctive feature of China’s economic growth, and the contribution of productivity to China’s exceptional economic growth is unparalleled in the history of the growth of the wealth of nations. This is non-traditional thinking in terms of Adam Smith’s concept of the invisible balancing of free market forces.

For these reasons, China’s rapid economic growth inspires many Africans. The next natural question is therefore, ‘How did the Chinese create this impressive productivity record?’ Compared to Eastern European and Latin American countries, China grew very fast while they lagged behind or even went into crisis. How did China grow this fast? Can Chinese growth serve as a blueprint for other countries? Broadly speaking, renowned economist such as Jeffery Sachs and Wing Woo believe it is possible to copy the development road map in other countries, whereas others such as Philip Naughton and Ronald Mckinnon believe the opposite. I believe that there are many similarities between the pre-1978 China and many African countries, including large populations with insufficient food and clothing, high levels of illiteracy and a large agrarian population.

Zuliu Hu and Mohsin Khan in their article entitled ‘Why is China growing so fast?’ point out that state directed reform began with the formation of rural enterprises, investment in manufacturing, and highland middle-level training.[4] A series of reforms that were introduced and directed by the state accelerated the increase in productivity. This is the first unconventional characteristic of Chinese economic growth. The second reason for this growth is that it did not come from the forces of the free market, as conventional theories of economic development dictate, but from state-led economic reform. Hence, productivity and the role of the state in economic development are unprecedented in conventional economic growth theory as prescribed by international institutions of financial governance such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The transformation of the economic base from agriculture to manufacturing and higher prices for agricultural products have moved many people out of the highly congested agriculture sector.[5] The industrial sector has also shown gradual development from a primary industrial base to an advanced one. To achieve a 12% reduction in primary industry, 20% of the Chinese workforce shifted from agriculture to industry.[6] Expanding protection and space for private property, welcoming foreign investment in areas where Chinese cannot effectively participate, tax waivers for foreign investment, enhanced job opportunities, and joint ventures enhanced the competiveness of the Chinese economy at the global level. While the prices of agricultural products were freed, prices of others products were in many ways controlled.[7]

For countries with a large segment of the population underemployed in agriculture, the Chinese example may be particularly instructive. By encouraging the growth of rural enterprises and not focusing exclusively on the urban industrial sector, China has successfully moved millions of workers off farms and into factories without creating an urban crisis …. As such, they offer an excellent jumping-off point for future research on the potential roles for productivity measures in other developing countries.[8]

In a nutshell, the lessons from China’s economic growth could be summarised as follows:

(1) Economic growth does not necessarily have to follow one path, that of unchecked invisible free market forces of the Adam Smith type, and there is another path, albeit an unconventional one.

(2) Economic growth reduces poverty.

(3) Domestic economic policy choices determine the growth of a country.

(4) Economic growth should not necessarily lead to the marginalisation of the role the state can play, and the state can make an indispensable contribution to economic growth. For instance, state-directed public–private sector partnerships for strategic national interest-led investment is important even in areas that are not profitable. For many economists, the current (2008– 09) global financial and economic crisis has proved the extremely important role of the state in regulating and stimulating the economy.

(5) State-led market friendly incentives particularly in agriculture are the basis for transformation towards a manufacturing and service economy.

(6) The productivity of the workforce can be more important than capital.

(7) For the urgent developmental needs of Africa, such as infrastructure, health and education, which have quick and visible impacts on the population, the Chinese development model is as equally useful as the China–Africa partnership. For Africa, the partnership with China is free of conditionalities. The traditional Western conditionalities are irrelevant to economic development and thus have undermined the role of the state in the socio-economic life of African countries. In order to clearly explain the potential of Chinese lessons for Africa, I shall first give some information about the economic performance of China, compared to India and other countries like the United States. Then I shall describe what kinds of constraints are affecting China and India and how they have removed these and could remove the remaining constraints. This, I hope, will help in identifying the main lessons for Africa from China and India, as many of the constraints faced by India are similar to those faced by Africa.[9] By looking at data such as levels of credit in relation to GDP, years of schooling of the labour force, infrastructure indicators, institutional quality, export dynamism, returns to capital, the cost of capital, credit rationing, the cost of financial intermediation, returns to human capital, etc. of China and India, I will try to distil the main lessons from the Chinese and Indian economies for African countries.

For this purpose, I shall use the Growth Diagnostic Tree methodology developed by Ricardo Hausmann, Dani Rodrik and Andrés Velasco.[10] This methodology raises questions as to why growth is constrained. Is it because of the high effective cost of finance or because of the lack of returns to private investment? Is it because of insufficient domestic savings or restricted access to foreign savings? Is it because of poor infrastructure? Is it because of the kinds of exports? Does the country produce ‘poor’ or ‘rich’ country goods? Or is it because of the institutional and legal governance of the economy? Is the judicial and legal system functioning effectively to enforce contracts? These are called binding constraints.

To adapt George Orwell’s famous expression, all constraints are binding, but some are more binding than others. Most binding constraints are bottlenecks to economic progress causing the highest degree of distortion. The payoff in enhancing the performance of the economy is very high if such constraints or distortions are removed. The higher the return from removing the constraint, the more binding the constraint is to the economy. Some booming economic activities such as the software industry in India or unusually high savings in China imply that these dynamic sectors of the economy are trying to ‘hoop jump’ the binding constraints. As we will see in the case of India, the most binding constraint is poor hard infrastructure, whereas in the case of China, low domestic consumption has increased saving due to social insecurity. By looking at the most problematic areas of economic activity, one can diagnose these binding constraints.[11]

Consequently, the kind and priority of reforms a country should take in order to grow faster could be identified by identifying these most binding constraints. The analysis and conclusions in this brief paper are supported by tables, graphs and comparisons.

2. Comparison between China and India and other significant countries

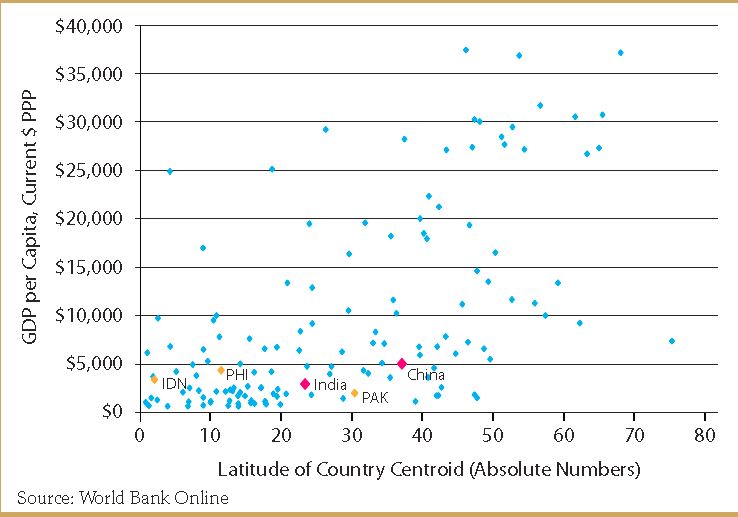

Around two decades and ago, India and China had similar GDP growth. Currently, these countries are among the top ten countries with high growth rates. In 2005, India’s GDP reached 8.5% and the average GDP growth rate for 2000–04 was about 6.2%. While India is growing at an average rate of 6–8%, China is growing at a rate of 9–11%. Even if it is developing rapidly, India’s GDP growth is lagging behind China’s. The reason is summarised by Janson Overdorf: ‘Conventional wisdom has always held that India failed to become an export drive dynamo on the Chinese model because its democratic system could not deliver the hard infrastructure and soft labour laws needed to manufacture competitively.’[12] China is the fifth-largest economy in the world and will soon become the fourth largest. For the past ten years, India’s unemployment rate has been around 9.15% (see Figure 1). China is richer than the four other Asian countries combined — India, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines. Both China and India, however, have large populations.

One of the differences between India’s reform and China’s is that while India was overly focused on the form of institutions, China’s reforms centred on the function of such institutions. Power was devolved to provinces, and city leaders encouraged competition, productivity and innovation. The state also protected state enterprises while genuinely encouraging the private sector. Comparing their income per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP), China is relatively the richest within the group with per capita PPP income of $4,995. Indonesia and the Philippines are richer than India, which has a GDP per capita ($2,909) that is below the average ($3,512). India is richer only compared to Pakistan, which has a GDP per capita of $1,971. The GDP growth rate of India and Pakistan is far greater than that of Indonesia and the Philippines.

China has the highest GDP per capita compared to the other countries, as shown in Figure 1. We will now examine how this fact correlates with other factors that might affect GDP per capita.

In China’s case, the years of schooling of members of the labour force seem to show that it is on par with GDP per capita. China also has the second-highest number of years of schooling compared to the Philippines, which has about 6.7 years of schooling per member of the labour force, whereas the figure for China is around 5.4 years. With the exception of the Philippines, which has more years of schooling but lower GDP per capita, the rest show a correlation (seemingly a proportional one) between years of schooling and GDP per capita. Indeed, compared to the other countries and with the exception of China, the Philippines has the second-highest GDP per capita. This is inconsistent only if we compare it to China, which has higher GDP per capita than the Philippines, but fewer years of schooling per member of the labour force.

PHI = Phillipines; IDN = Indonesia; PAK = Pakistan (applies also in other figures given below).

China and India are ahead of the rest with regard to indicators of the prevalence of the rule of law. Nonetheless, from what these indicators show, even if India has lower GDP per capita compared to China, the Philippines and Indonesia, it is a country where the rule of law is relatively prevalent. Pakistan has lower GDP per capita than Indonesia, but the graph in Figure 3 shows it has better rule of law. It is therefore very difficult to see the correlation in terms of the relationship between the rule of law and per capita GDP.

Again, in terms of these countries, the correlation between a country’s latitude (geographical position) and its GDP per capita is not clear, or perhaps there is no correlation. China’s case shows some consistency. Nonetheless, the Philippines has a lower latitude than Pakistan and India, but it has a higher GDP per capita. Even Indonesia’s case is extreme, since while it has the lowest latitude of all the countries compared, it has the third-highest GDP per capita, following China and the Philippines.

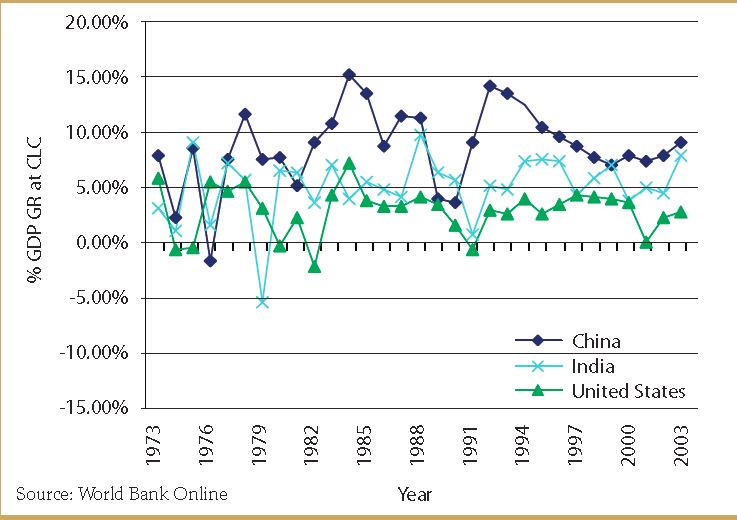

As shown in Figure 5, the GDP growth rate of both China and India is greater than that of the United States in terms of constant local currency (CLC), even if that may not be true in terms of PPP. Moreover, as indicated by Figure 5, India is catching up with China. China and India, followed by Pakistan, have greater GDP growth rate at CLC. At the end of 1980s and in the early 1990s, Indonesia did better than all of them, and China showed a great increase between 1991 and 1995. In the past ten years, China and India, followed by Pakistan, have been growing very rapidly.

As Figure 7 shows, China and India have a higher GDP growth rate compared to the other countries. China has a higher investment ratio compared to India. As Figure 8 indicates, China has an investment ratio of 32–42%, while India has a ratio of 22–26%.

With the exception of the Philippines, which has a low investment ratio but a higher mean GDP per capita, clearly the investment ratio and GDP per capita seem to show some correlation. China, Pakistan, Indonesia and to some degree India show a positive correlation between investment ratio and mean GDP per capita. Both China and India have higher secondary school enrollment levels than other significant countries and slightly lower enrollment than that of the Philippines. This figure is consistent in the case of China and higher in the case of India compared to the GDP per capita of other countries. China, as we have seen, is growing faster than the other significant countries. Chinese schooling is not elitist, but rather public and in line with public demand.

Clearly, it is not economic freedom or free market forces that led to the spectacular economic development in China and India. Unlike countries such as Argentina and Brazil that swallowed the prescription of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank to limit the role of the state, as shown in Figure 12, China and India do not have the highest mark in terms of economic freedom, but they have grown faster than the rest of the world.

3. Binding constraints on the Chinese economy

There are various constraints on Chinese growth. Low domestic consumption, a weak non-manufacturing sector, and disparities and inequalities are the major ones.

3.1 Low domestic consumption

The most binding constraint that China is facing now is excess savings or insufficient consumption. National saving rate reached 50% of GDP in 2005. In the same period, household consumption accounted for only 38% of GDP, the lowest share of any major economy in the world. For example, in the United Kingdom, the household consumption share of GDP was 60%, while in India it was 61%.

These figures for China have been partially attributed to the nearly nonexistent social security system. Therefore, measures to stimulate domestic consumption are very important. These include the creation of social security schemes, a reduction in the saving-investment surplus, and an increase in the efficiency of investment. Some elements of the long-term rebalancing package are also useful in containing investment now, including shifting the composition of fiscal spending away from capital spending towards education, health and social security.

The sooner the rebalancing starts, the sooner the short-term challenges will be dealt with. Demand has to be increased by domestic consumption funded by the high savings. Here it is important to understand that the structure of demand and the efficiency of investments are critical for a sustainable growth path in the long run. Rapid growth is more likely to prove sustainable if it is generated more by expanding household consumption nationally and less by surging investment by Chinese companies and a ballooning global trade and current account surplus.

3.2 Imbalance between manufacturing and service provision, and the re-evaluation of the exchange rate

Measures to increase the relative attractiveness of providing services (non-tradables) over manufacturing production (tradables) are other reforms needed to remove some of the constraints. Shifting the composition of growth away from investment and exports towards consumption would help address the short-term challenges that China faces.

3.3 Regional disparities and social inequality

Social peace depends on the equitable distribution of the benefits of economic growth throughout the country. Regional growth disparities and increasing social inequality could hamper sustained growth, as access to finance increases in areas where there is wealth and assets to serve as collateral: money attracts money. Income is generated in rapidly developing regions, particularly the coastal areas, and talent attracts talent just as capital attracts capital. The government needs to enhance access to finance in areas where less collateral is available to banks. In summary, several questions related to high trade surpluses and exchange rate re-evaluation need to be dealt with in tandem with fiscal expansion. The challenges need to be addressed by a combination of monetary and exchange rate re-evaluation, fiscal policy, and institutional reforms. Removing these binding constraints could unleash the forces for economic growth again.

3.4 Less efficiency in the use of resources

Multi-factor productivity growth, a critical contributor to economic expansion in all economies, averaged almost 4% per annum in the first years of China’s economic reform (1978–93). While still high by international standards, this pace has slowed down to only 3% since 1993. The slowing pace of factor productivity growth can be attributed in part to over-investment and the emergence of excess capacity in a number of important industries such as the ferroalloy industry, where capacity utilisation in 2005 was only 40%. Similar excess capacity has emerged in the steel industry, aluminium, autos, cement, coke and others. As a result, prices are now falling, which has an adverse impact on the profitability of the industries, which presumably has impaired the ability of some of these industries to service their debt. In general, excess investment in some sectors, leading to excess capacity and falling prices, could create a new wave of non-performing loans that would erode the substantial balance sheet improvements of the state-owned banks.

4. The most binding constraints on the Indian economy

The following four constraints are the most binding on India’s economy: bad infrastructure, a huge deficit, difficulty in doing business, and low FDI and a weak financial system. The binding constraints are listed in a ranking starting with the most binding to the least one so as to prioritise the reform efforts.

4.1 Low return on economic activities due to bad infrastructure

One very useful means of identifying the most binding constraint is to see if India’s economy is trying to evade a trap by ‘hoop jumping’. India’s economy is specialising in exportable products without acknowledging the need for physical transport facilities or infrastructure. The complementary factors of production (in this case, bad infrastructure in terms of transportation, roads and ports) seem to be the most binding constraint for India. The information technology industry and business outsourcing in software and call centre services have grown faster than the export of manufactured goods and services. These economic activities must have a good return to grow quickly.[13]

For this reason, the Indian economy has a skewed growth pattern and a concentration on sectors such as software services. The boom in these sectors seems to be related to their capacity to evade traps related to cost effectiveness. These sectors are skills intensive and employ only those with high professional training. Small and labor-intensive industries are growing much slower, but could be a source of employment and growth. The high cost of transportation is a disincentive to many export-oriented manufacturing companies. According to a World Bank report, in India electricity supply interruptions cause an 8.4% loss of income for manufacturers.[14]

According to WDI, India’s infrastructure is ranked 53rd among 75 countries evaluated for the quality of infrastructure (see Figure 16). Its electric supply quality is one of the lowest, ranking 2 out of best possible score of 7. The electricity price is one of the highest in the world and India’s median time for international mail delivery is the second highest. The driving speed between cities is very low and competitiveness in transportation is very poor. Bad infrastructure has been the cause of the sluggish expansion of exportable goods that are not infrastructure intensive, and instead, skills-intensive industries like business outsourcing and the software industry have grown rapidly.[15]

Infrastructure shortages have particularly hindered the growth of export oriented manufacturing and value-added agriculture that integrate into global supply chains, and need good roads, ports, airports, and railways as well as reliable power and water to prosper.

Thus, if it was not for infrastructural costs, India could have grown more by exporting ‘rich country goods’. Production of exportable goods, including agroindustry products, which are labour intensive, need better and high-quality transportation infrastructure and sustainable supplies of inputs such as electricity and water. Bad infrastructure is attributable to insufficient investment in complementary public goods. Indeed, for this reason, research shows that India needs 3–4% of its GDP to be invested in infrastructure in order to sustain its growth. Infrastructure is one of the most binding constraints on India’s economy, which, if not improved, could hold the economy back. Moreover, apart from the highly skewed growth in sectors requiring less infrastructure, regional and income inequality in India is attributable partially to poor infrastructure. Regions in the vicinity of ports gain most of the benefits of growth rather than other regions. Educated and skilled Indians, who only make up 20% of the population, are getting most of the employment. Unemployment of low-skilled people who cannot join the software industry is on the increase. Micro risks (difficulty in doing business) and macro risks (the fiscal deficit) are the other two bottlenecks in terms of government failures that negatively affect economic growth India.

There are at least four times more unemployed people (around 35 million) than are employed in the organized private sector. Firms with more than 100 workers consider labor regulations to be as constraining to their operation and growth as power shortages. Reference: World Bank, India Country Review 2006, pp. 36–40.

4.2 Fiscal deficit

The fiscal deficit is one of the biggest constraints that contribute to the low appropriablility of economic activities. India’s fiscal deficit was 10% of GDP in 2005.[16] This is a very high level of public debt. With a high debt-to-revenue ratio, the deficit could have led another country to high volatility and a financial crisis.[17]

However, India shows low volatility due to its strict regulation of the rupee, the fixed rates of the financial market and high foreign currency reserves (more than $160 billion).[18] Nonetheless, for healthy and longterm stability, India has to come to terms with its fiscal deficit and the government has to tighten its belt and ensure fiscal responsibility at all governmental levels of the state.[19] Hence, India is facing a huge deficit that inhibits the government from spending in areas such as infrastructure that are essential in sustaining and accelerating growth. It also dries up the resources accessible to the private sector. As fiscal irresponsibility is a form of government failure, reform of this area is within the realm of government.

Clearly, improvements to infrastructure will be costly, aggravating the deficit. However, such an investment in complementary public goods would pay huge dividends in terms of development. Since any deficit due to investment in infrastructure will accelerate the overall development of the economy, fiscal responsibility should focus on other areas of spending that could be reduced or made more efficient.

4.3 Difficulty in doing business

India is also notorious for its cumbersome bureaucratic public service and backlog in judicial processes. Under the low appropriablility and government failure branch of the Growth Diagnostic Tree, India’s government failure manifests itself in its cumbersome business-related processes and the inflexibility of the labour laws, delays in enforcement of which may take 306 days, and high trade tariff, which is about 22%.[20] In terms of doing business, India has very bureaucratic processes and huge amounts of paper work that take several months to complete.[21] In India, its takes 89 days on average to start a business, which is more than twice that of China and four times that of South Korea.[22]

India also has a rigid labour code, with one of the highest scores on the firing index, 90, compared to China’s, which is 40, and South Korea’s, which is 30.[23] The labour code is applicable to employers with more than ten employees and imposes heavy obligations on such employers. Thus, employers prefer to remain small or break up their function into smaller units to evade these heavy labour law requirements. India’s labour code is ‘among the most restrictive and complex in the world, protecting only the insiders’ and providing security only to those employed and disregarding its adverse effect on job creation.[24] India had both high average unemployment (about 9.15%) and a high average deficit (about 10%) for the period 1995–2005 (see Figures 17 and 18). The country has a large labour force and people are too poor to leave their employment in the absence of social security, and the army of unemployed serves as a gatekeeper for jobs. Hence, those in employment stick to their jobs. Disputes over land titles and deeds are rampant and the enforcement of contracts particularly related to land takes several months, if not years.

The McKinsey Global Institute argues that land market distortions account for about 1.3% of lost growth per year.[25] Corruption is found to cause 37% of the difficulties in doing business. Customs processes are very lengthy (see Figures 19 and 20). Difficulty in doing business is therefore a binding constraint associated with government failure. As the Indian taxation system is ineffective, the revenue from taxation is very low. This affects the informal employment sector, which is very large, as it allows employers to evade the rigid requirements of the labour code. This constraint continues to negatively affect India’s economic growth. Removing these government failures would not only have a huge payoff in pushing the growth of the Indian economy, but would also help in ensuring the sustainability of the growth that is achieved.

Figure 17: India’s recorded unemployment, 1995–2005 (%)

Figure 18: India’s total labour force and population, 1995–2005

Figure 19: Difficulty of doing business in India: Days to clear customs

Figure 20: Doing business in India and China, 2001

Figure 21: India: Current FDI in relation to GDP, 1995–2005

4.4 Low FDI flows and weak financial system

Low FDI flows and a weak financial system is another most binding constraint on India’s economy (see Figures 21–24). The country has very weak access to international finance. India depends on domestic saving, local finance and public borrowing, which has led to its huge fiscal deficit. Bad international finance could be taken as one of the major binding constraints, but this seems to be deliberately sought by the government to encourage the growth of domestic financing. Nonetheless, in the long term, India needs to attract more FDI to become and remain more competitive and has to loosen some of its financial regulations.

Figure 22: FDI as a % of GDP in China and India, 1991–2002

Figure 23: FDI’s share of GDP in selected countries, 2000

Figure 24: India and China in terms of the Global Competitiveness Index and the macro economy, 2006–07

5. Recommendations

The bottlenecks listed above are ranked in terms of their distortion effect(s) on the economic growth of the countries concerned. The more distortion a binding constraint causes to the economy and the more its consequences are removed, then the more urgent a priority area it is for change. This ranking of binding constraints is very useful for various reasons, inter alia, to prioritise the areas of reform and to determine the allocation of resources.

It would be very difficult to give general recommendations for a continent like Africa. However, a very general recommendation is that the main lesson from the Chinese and Indian growth models shows the vital contribution of productivity if capital is almost non-existent. Growth both in China and India shows that market-oriented but state-led economic reform can deliver much needed economic growth.

5.1 Concluding remarks and recommendations for African countries

Since the 1978 commencement of reform, China has been the fastest-growing country in the world. Its exceptional growth has been characterised by high savings, high investment, managed urbanisation and internal migration, very low productivity in agriculture, and record levels of productivity in manufacturing. Similar to other growing Asian economies, Chinese economic reforms in education, manufacturing and agriculture were not elitist or selective, and were superior in quality. The urgency of the demand for infrastructure, communications technology and development projects in general inspires Africa to learn more from China, and to work and trade with its enterprises. The spectacular Chinese economic development was based on state-led economic reform rather than political reform. Pragmatic political economic considerations with regard to state reforms were the drivers of growth. The reforms focused on the effective protection of property and contract enforcement, and strict government control on prices and financial institutions. The reforms were gradual, but well sequenced to remove constraints whose removal would have a multiplier effect. Dan Rodrik says the Chinese focused ‘first on agriculture, then industry, then foreign trade, now finance’.[26]

5.2 Areas of priority for reform in Africa based on the Chinese and Indian experiences

Rule for reform: Identify binding constraints, target the most binding constraint, then prioritise and sequence reforms based on potential returns. Since it is almost humanly impossible for the government to simultaneously eradicate all constraints that are holding back a country’s development, it is suggested that the top priority for the government should be to focus on those bottlenecks that if removed would give higher payoffs than dealing with the other problems the country is facing. Hence, the recommendations require the allocation of the government’s resources according to the degree of distortion a constraint causes to the economy, and the growth return (payoff) of removing and tackling such a constraint. Note that potential gains of removing such bottlenecks and performance gaps are mutually reinforcing. The following areas of reform could be identified as priorities for Africa.

Africa has to invest 3–4% of its GDP on infrastructure to sustain around 8% growth. As discussed above, the lack of infrastructure is the leading constraint on rapid growth and spreading this growth more widely. Bad infrastructure has usually resulted in a skewed pattern of growth that may not be sustainable. If infrastructural constraints are removed, several estimates show that an economy will grow 4.5% faster. Governments have to spend more in sectors such as infrastructure to expand exports. The cost of investing in infrastructure would increase the fisical defict, which itself is a constraint. To mitigate this side effect, the government has to invite public and private investments in infrastructure. Whatever the case, the return from public expenditure to remove the infrastructural constraint would be greater than the cost.

To effectively and efficiently improve the infrastructure, governments should build up the implementation capacity of authorities in charge of infrastructure. To remove these constraints, it is essential to build the implementation capacity and efficiency of the public services. This is particularly relevant to the improvement of infrastructure. The implementation capacity of those authorities in charge of infrastructure should be enhanced. The process of outsourcing and contracting works and the bidding process have to be re-engineered. In general, governments have to design a comprehensive public service reform programme of all civil service institutions in charge of infrastructure.

Consolidate a plan for comprehensive reform of the public service. This could be the relatively easiest of all reforms, as it is entirely within the government’s will and competence. The reform of public services to eliminate cumbersome bureaucracy and corruption is essential to improving doing business in Africa. It should aim to make doing business very easy. Court backlogs and proceedings have to be reduced markedly so as to make disputes over land titles and deeds as well as enforcement of contracts short and efficient. Through civil service reform, it should not be difficult to remove constraints related to difficulty in doing business if this is set as a priority of government programmes.

Reform of the taxation system would assist in balancing the fiscal deficit, but would also allow the government to spend on essential public investments with high social return. Basically, to cover the cost of investment in infrastructure, African countries have to reform their taxation and revenue architectures. Since African taxation systems are almost non-existent and ineffective, the institutional architecture for revenue collection and culture is absent. The informal employment sector, which is also very large and evades the rigid requirements of the labour code, has to be drawn into the taxation system.

——

End notes

1/ The researcher is currently serving as programme coordinator at the African Union Commission and executive director of the African Rally for Peace and Development. He holds an MPA from Harvard University, an MSc from Oxford University and an LLB from Addis Ababa University. This article is a revised version of a course paper submitted to Harvard University in 2007.

2/ Wang Mengkui, ‘China’s course of modernization and its outlook’, in China’s Economy. China Intercontinental Press, 2004, pp. 4–6.

3/ Zuliu Hu & Mohsin Khan, ‘Why is China growing so fast?’, Economic Issues. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 1997, p. 1.

4/ Ibid.

5/ Ibid., p. 3.

6/ Zhang Jun, ‘Economic restructuring: From planned economy to market economy’, in China’s Economy. China Intercontinental Press, 2004, pp. 46–47.

7/ Hu & Khan, op. cit., pp. 3–4.

8/ Ibid., p. 4.

9/ McKinsey Global Institute, Accelerating India’s Growth through Financial System Reform. McKinsey Global Institute, May 2006.

10/ Ricardo Hausman, Dani Rodrik and Andrés Velasco, Growth Diagnostics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

11/ Dani Rodrik, ‘Institutional arrangements and economic growth’, George Mason Guest Lectures, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, March 2006.

12/ Janson Overdorf, ‘India’s development’, Newsweek, 19 January 2009.

13/ ‘What’s so special about China’s exports?’, John F. Kennedy School of Government Faculty Research Working Papers Series, January 2006.

14/ Ibid., p. 130.

15/ World Bank, India Country Review 2006, pp. 36–40

16/ Ibid.

17/ Ricardo Hausmann, The Challenge of Fiscal Adjustment in a Democracy: The Case of India. Kennedy School of Government & IMF, 2004, pp. 41–42. 18 World Bank, 2006, op. cit.

19/ Ricardo, op. cit., pp. 41–42.

20/ World Bank, India Inclusive Growth and Service Delivery: Building on India’s Success, Development Policy Review, report no. 34580-IN, 15 June 2006, p. 127,

21/ Ibid., p. 129.

22/ World Bank, World Development Indicators and World Bank Doing Business Database, 2005. 23 Ibid. 24 World Bank, 2006, op. cit., pp. 36–40. 25 McKinsey Global Institute, op. cit. 26 Rodrik, op. cit.

23/ Ibid.

24/ World Bank, 2006, op. cit., pp. 36–40.

25/ McKinsey Global Institute, op. cit.

26/ Rodrik, op. cit.

***********

*Mehari Taddele Maru is a specialist in international human rights and humanitarian law, an international consultant on African Union affairs, and an expert in Public Administration and Management.

*Originally published on Bulletin of Fridays of the Commission Vol 3 No 1 on January 2010.