Testimony on the Plight of Internally Displaced Peoples (IDPs) in Africa and the imperative to Engage African States according to the Kampala Convention on the Protection and Assistance to IDPs.

Venue: UN Security Council

New York, May 30, 2014.

Speaker: Costantinos Berhutesfa Costantinos, PhD – Trustee, Africa Humanitarian Action, www.africahumanitarian.org. Professor of Public Policy, AAU Graduate School, [email protected].

Engaging African Polities in Advancing Self-esteem of & Protection & Assistance to IDPs – “The Kampala Convention”: Cases of Central African Republic & South Sudan

Summary presentation to the UNSC:

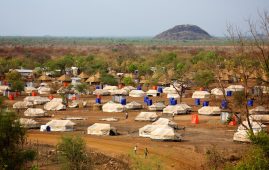

Central African Republic and South Sudan are new entrants to the litany of human displacement & despair in Africa, so much, so the repeat of the Rwandan Genocide would be too ghastly to contemplate. This is happening despite the fact that protection & assistance to the IDPs is central to the African Union Kampala Convention. African states have legally committed themselves to promote & strengthen regional & national measures to prevent or mitigate, prohibit & eliminate root causes of internal displacement as well as provide for durable solutions. Furthermore, they have agreed to establish a legal framework for preventing internal displacement, protecting & assisting IDPs, to establish a legal framework for solidarity, cooperation, promotion of durable solutions & mutual support between the States Parties. In this sense, they have pledged to provide for the obligations & responsibilities of States Parties & provide for the respective obligations, responsibilities of stakeholders with respect to the prevention of displacement and protection of, and assistance to, IDPs.

Nonetheless, the AU Conventions have a history of implementation deficit. They seem within reach, only to elude; they look readily tractable, only to resist realization. As we look intently into an emptiness of gruesome genocide in SS & CAR, the UNSC must focus on the most vital action of addressing the root causes of displacement, restoring security & elevating participatory humanitarian action. It must augur its decisions on soft power of conflict management approaches, alliance of ethnics and religions, peace, reconciliation, shared values, vision and resources of civil society, and Public Private Partnerships and implementation of ‘right to protect’ resolutions.

Chair, ladies and gentlemen,

Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan (SS) are new entrants to the litany of human displacement and despair in Africa. The repeat of the Rwandan Genocide is all too ghastly to contemplate (Costantinos, 2014; ICG, 2013; OCHA, 2014 & UN Security Council, 2010). This is happening despite the fact that protection and assistance to Internally Displace Persons (IDPs) is central to the African Union Kampala Convention. Let me begin by commending the Union for its engagement of Crisis Affected States and Societies (CAS) in the Kampala Convention. In focusing on the context and broader environment of conflicts in Africa, three questions emerge:

-

How do states go into a crisis: there are rapid onset, slow onset, natural or human made crises and what are the circumstances under which a breaking up state affects CAS?

-

In seeking the implementation of the Convention, what mechanisms and mediums are used to express CAS injury, resolve and expectation? How are their indigenous coping mechanisms and adaptive strategies that constitute their resistance and resilience articulated to preserve their self-esteem, integrity and innovativeness;

-

How do humanitarian pundits articulate mediums for engaging the Kampala Convention?

It is easy to flow with the current trend and advocate engagement of the Kampala Convention as a desirable paradigm. Nor is it difficult to make normative judgments about how agencies should behave if engagement of the Kampala Convention is to grow into a positive agent of change. Nevertheless, it is not so easy to conceptualise the Convention as a working process, which balanced against strategy, determines what makes for real, as opposed to vacuously formal processes.

As a way of contributing to the overcoming or lessening of these difficulties, humanitarians may theorise engagement of the Convention as the dynamic interaction of policy, strategy, organisation and process. It is possible to see such engagement as the playing out of objective and critical standards, rules and concepts of economic, social and political conduct in the goals and activities of all participants, those of officials and/or combatants who make and administer the rules as well as those of ordinary citizens. The issue here is not simply one of application of the Kampala Convention to particular activities. Nor is it one of dissolving agent-catered strategies into objective principles and norms. It is rather the production or articulation of process elements and forms within and through the strategic (and non-strategic) activities of participants.

1. How does one view the Kampala Convention’s process openness

There are countervailing currents and pressures within the intersection of participating organisations and groups, which tend to work against or limit engagement of process openness. At the structural level, a certain hierarchy of agency is evident within the network of participants, such that humanitarian actors assume primary position relative to CAS. For example, with massive financial and technical capacity at their command, Development Banks are major players with whom recipients of their aid must come to terms with. This hierarchy of agency effectively places CAS in the ‘participatory’ network in positions of subordination. It also places limits on the range of agents and forms of practice, which can be networked through their engagement. Thus, although their engagement is crucial for human security, local groups tend to be neglected or marginalised.

Engagement of African states in the Kampala Convention will commonly be characterised by a number of distinctive and shared additional elements, including national and cultural values, traditions of political discourse and arguments and modes of representation of specific interests and needs. These elements, or complexes of elements, will tend to assume varying forms and enter into shifting relations of cooperation, competition & supremacy. Engagement of states in the Convention tend to be unsettled and, at times, unsettling. Particularly at the initiation of rapid-onset crisis, they are more likely to be uncertain rather than stable structures, ideas and values. A determinate order of institutions, powers and interests operate through complexes of engagement ideas and values, filling out, specifying, anchoring and often shortcutting their formal content.

Here, conceptual possibilities may be left unrealised, or sub-optimally realised, insofar as the elite are preoccupied with filling out those spaces of uncertainty in humanitarian thought, discourse and action that alternative ideas would occupy in the course of their own engagement. It has to do with creating conditions for the existence of the broadest possible range of opinions and sentiments. In this regard, we can ask:

-

Are all ideas and values of the Convention allowed to contend or are there unwritten codes of African states, which prevent or hinder such actions?

-

Do the views and perspectives of crises societies have a significant and legitimate place in the Convention? Is good faith criticism of the engagement strategy construed as hostile to it?

Questions such as these are important in examining and assessing the ideological basis for implementing the Kampala Convention. Nevertheless, as important as it is, this is only one context or level of analysis of the breadth and depth of the humanitarian terrain of ideology. There is another level of analysis, concerned with the extent and nature of openness of distinct constructs to one another, with modes of articulation of given sets of ideas and values and of representations of specific issues relative to the others. The concern here is not so much the number and diversity of ideas, values and opinions allowed to gain currency in the Kampala Convention as modes of their competitive and co-operative articulation. For example:

-

Does the Convention enter local processes as an external ideology, constructing and deploying its concepts in sterile abstraction from local state priorities?

-

Does it come into play in opposition or in cooperation to political values & cultures?

-

Does this signify change in terms of the transformation of the Convention into an activity mediated and guided by objective standards, rules and principles?

-

In the establishment of rules of engagement of the Convention, do African states equate their articulation with the broad-based concepts, norms and goals of ‘humanitarianism’, which should govern their actions?

Indeed current analyses of engagement of crisis-affected societies in the Convention are generally marked by the tendency to narrow such an engagement to terms of immediate, not very well considered, action, naïve realism, as it were. Problems of grounding the Convention realistically rather than simply as abstract promise obtain little attention – because promising too much could be as deadly as doing nothing. This leads to a nearly exclusive concern in certain institutional perspectives on engagement in the Convention with generic attributes of social, economic and political organisations and consequent neglect of analysis in terms of their specific strategies and performances. Ambiguity as to whether IDPs are the agent or object of engagement and their inadequate treatment in the objectives, strategies and roles of the Convention is also a challenge…

Findings from the process-oriented research point to the fact that soliciting IDP voices is one dimension but listening to what those voices say, is a much deeper expression of their perceptual encounter in its purely subjective bearing. At the outset, our research questions augured on three basic points of departure. One was to find out the circumstances under which a state that is breaking up affects populations in CAR and SS. In addition, we wanted to know how within the remit of the Kampala Convention, people could elicit their coping mechanisms and adaptive strategies. These constitute resistance and resilience to the destitute life, uttered across various societies with a view to promote their self-esteem, integrity and innovativeness. Furthermore, what are the mechanisms and mediums the Convention uses to express injury, resolve and expectation? Indubitably, these involve cultural manifestations, socio-legal and political arenas, ethical articulations & the meanings of voice.

2. The context for dialogue, partnership and interface

Far more critical in determining both the level and quality of dialogue and strategic partnership within the Kampala Convention is the political and economic context in which fragile states find themselves. The context for dialogue, partnership and interface has largely been determined by agencies rather than the authors of signatories of the Kampala Convention. Hence:

-

New ‘rules’ of engagement must be based on the fundamental perception, that people and their participation can be the handmaiden of the Kampala Convention. This underpins a paradigm shift of a negotiating trend towards a total reorientation of both donors and recipients. As stated in the Kampala Convention, it is about re-imagining the role of states and societies in human security, for which experiences have already been got, some tantalisingly avant-garde, while some were wrong, but unwittingly instructive.

-

The Security Council members must be aware of the various kinds of organisations that play a leading role during different phases of crisis and take a snapshot of the organisational landscape, compiling a record of basic data on all local organisations. This must necessarily include information on the position taken by protagonists on the political and social contestation, identifying, and underscoring the importance of organisations who have a higher stake. In order to set the context, implementers of the Convention must study the crisis state’s distinctive institutional history, focusing on the balance of power between the interactions of civic, state and international organisations.

The relevance of Kampala Convention can be explained with reference to two institutional factors: compassionate institutions and rules. The central hypothesis is that the relative strength of local institutions determines the rules of the game in humanitarian engagement and human security. The institutional characteristics that apply to CAR & SS are organisational autonomy, organisational capacity, organisational complexity and organisational cohesion. On the rules of engagement, effectiveness in engaging the Kampala Convention can be attained only if full accountability, transparency and predictability are assured. Invariably, this entails political culture development, a process of institutional learning, in which organisations develop a new and stable set of mechanisms for engaging the Kampala Convention.

3. Appeal to the Security Council

While many proposals for remedial action have been formulated for addressing vulnerability and peoples’ poverty that haunt the region, real commitment to collaborative processes at inter organizational level has always been limited. Mobilizing the action required has also remained a daunting challenge, as many practical and structural constraints militate against commitment by individual groups to inter organizational initiatives nationally and regionally. The tragedy, which took such a heavy toll of life over the past years, has highlighted the fundamental weakness of the peace, security and development strategies. Many conventional and preconceived notions have been questioned. Efforts have also been made to estimate the risks more accurately and to make adequate preventive measures. The role of AU Conventions has been harshly tested. The need for collective learning about responses and the responsibility to those whose suffering provided the basis for that learning will never be more urgent than now.

Unfortunately, such lessons, which may be learned through the shocks administered by an uncompromising reality, are rarely translated quickly into personal or organizational memories and the inherent will to change. The reasons for this are sometimes rooted in human inertia, weakness, and self-interest. They are equally often the products of a genuine confusion about how to act most effectively in an environment that seems to be growing more complex. These are stark examples of a failed humanity that have become a new insignia of ‘bestiality’. They deserve much better handling.

The UNSC must act and now!

The need for the fundamental change on how the global community deals with the internecine crises must change. It must encourage appropriate action for promoting and managing an enabling environment for mainstreaming peace, security a developmental response in the drive for human development and popular participation – people acting as citizens of a political society, reinforcing ownership and ensuring continuity. We advocate for the development of think tanks that would set the stage for the paradigmatic development of internal models of growth and human welfare. To every crisis, there always seems to emerge a solution that is smart, simple and immoral that tend to have a linear way of thinking that is inadequate to unravel the many complex interrelationships underlying people’s insecurity. It is neither popular nor scientific. While conflicts often serve as vital stimulus for change, academia must be invited to develop multidisciplinary protocols and tools to stem the tide of clashes and forging the alliance of faiths, cultures & political groups.

4. Implementation of the Kampala Convention can be explained with reference to two institutional factors: political organisations and political rules.

The central hypothesis is that the relative strength of commitment of the African Union determines which rules of the Kampala Convention that are installed. Implementation of the Kampala Convention requires a plural set of political moves, which promote and protect rules of peaceful political participation and competition. In taking an institutional perspective, we assume that actors in the political system express preferences through organisations that vary in strength according to their resource base. Relevant organisations are found both in society, where they represent and aggregate individual interests and in the state (Costantinos, 2014).

These organisations play a leading role during the implementation of the Convention. Concurrently, the organisational cohesion of the state becomes important; as the state may begin to fragment, as elite factions assert autonomy. Hence, implementation of the Convention can be attained only if legal texts are applied to ensure full accountability, transparency and predictability. Implementation of the Convention is a process of institutional learning, in which state and societal organisations develop a new and stable set of mechanisms to manage conflict peacefully. There must be consensus on the rules of the game, whether these rules are embodied in legal texts, or in less formal but no less real customs of politics, that may institutionalise uncertainty. It can succeed if and when all the political actors accept this uncertainty as preferable to the horror of conflicts (Ibid). Nonetheless, AU Conventions have a history of implementation deficit. They seem within reach, only to elude; they look readily tractable, only to resist realization. As these nations look intently into a void of horrifying genocide, the UNSC must focus on the most vital action of restoring security and humanitarian action.

5. Conflict management approaches that need the Security Council’s attention

Conflict management approaches derive from several basic premises about the nature of conflict, change and power. While attitudes about conflict can differ radically from one cultural context to another, it is assumed here that conflict is a normal process in society; that is, it is a given. The problem lies rather in how conflict is managed. Such an approach to conflict recognizes that the parties in a dispute have different and frequently opposing views about the proper solution to a problem, but acknowledges that each group’s views from its perspective may be both rational and legitimate. The discourse seeks to understand the configuration of social forces in the context of the always-impending social transformation of society based on the balance of such forces. The political interaction perspective on the other hand presumes that societal relationship as central to understanding the political dynamic in civic harmony. The neoliberal orthodoxy’s offshoots of this tradition have tended to treat civil society as if it were a replacement of class analysis. In order to un-pack some of the supererogatory aggregation of class categories, they have striven to expose a broader range of social relationships, strategic options and behaviour patterns within and among societies and, by that token, succeeded to mitigate the effect of structural determinism which usually accompanies class analysis. Ultimately, addressing citizenship issues implies thinking holistically, that is, looking at the big picture while maintaining awareness of the interconnected dimensions of society and polity. Hence, we need to look in tools that can avail the environment for peace and security.

6. Alliance of ethnics and religions that require the Security Council’s attention

Cultural-ideological premises for the alliance of cultures and arenas for forging the alliance of civilizations with tools for advancing the alliance of cultures and faiths:

A) Citizenship is the cornerstone of peace in the 21st Century

B) Strengthening a rights culture and democratic institutions

C) Independent human quality think tanks are indispensible here

7. Peace & reconciliation

Premises of Alternative Conflict Management (ACM) and the questions on factors that shape the ACM Process are grounded on the basic interests of combatants and the options that are presented at the negotiation table. Hence, the UNSC must commit to build fragile societies’ capacity, strengthen a rights culture and democratic institutions undergirding local governance and democratic devolution of power, and secure good economic governance. In this regard, the Kampala Convention must be supported by the mass of UN and AU declaration on peace, security, shared values, human development and human security.

8. Shared values, vision and resources of civil society

Shared values, vision and resources of community lead us to a fundamentally new value system based on justice, peace and the integrity of humanity. To a new understanding of sharing in which those who have been marginalized to take their place at the centre of all decisions and actions as equal partners and to identify with the poor and oppressed and their organized movements in the struggle for justice and human dignity in faith and society. These are demanding common tasks that build a community and the momentum for radical people’s participation. This is to bear witness to the mission of creation by identifying exposing and confronting at all levels the root causes, and the structures, of injustice, which lead to the exploitation of the wealth and people of the third world and result in poverty and the destruction of creation. This entails working for a new economic and political order to enable people to organize themselves, realize their potential and power as individuals and communities, working towards the kind of self-reliance and self-determination, which are essential conditions of interdependence.

9. The role of Public Private Partnerships (PPP)

PPP for development and participatory humanitarianism requires a plural set of organisations, rule of law, access to justice, labour and property and entrepreneurship rights. Political commitment and leadership, stakeholder ownership and public sector involvement are crucial to a sustainable reforms process and they must be in place prior to starting the process and maintained during implementation. A well thought out plan, with sector investments planned in parallel with reform of the utility, is essential. Governments must remain committed to sector investments and the state asset-holding company must be institutionally autonomous, professionally competent with clear financial targets. As part of the corporate social responsibility of the private sector, it is incumbent to mobilise it to undertake avant-garde humanitarian work(Costantinos).

********